Neither Fugitive nor Free: Atlantic Slavery, Freedom Suits, and the Legal Culture of Travel

Neither Fugitive nor Free: Atlantic Slavery, Freedom Suits, and the Legal Culture of Travel

Contents

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Preserving State Sovereignty Preserving State Sovereignty

-

Sectional Crisis and the Denationalization of Black Citizenship Sectional Crisis and the Denationalization of Black Citizenship

-

The Afterlife of Manuel Pereira in the Transatlantic Antislavery Campaign The Afterlife of Manuel Pereira in the Transatlantic Antislavery Campaign

-

The Circulation of Law and the Rise of Black Atlantic Radicalism The Circulation of Law and the Rise of Black Atlantic Radicalism

-

-

-

-

4 The Crime of Color in the Negro Seamen Acts

-

Published:July 2009

Cite

Abstract

This chapter describes the appeals to law made on behalf of black Atlantic mariners caught up in the workings of the Negro Seamen Acts which subjected all black mariners, regardless of national allegiances, to immediate imprisonment under threat of enslavement. British and American sailors instigated a number of legal actions, from Elkison v. Deliesseline (1823) to Roberts v. Yates (1853), to test the law’s constitutionality and secure its repeal, yet none of these cases reached the U.S. Supreme Court. Denied the courtroom, uneasy and shifting transatlantic alliances in the 1850s began to appeal directly to the public to address the failure of the law.

If any of you wish to know how free you are, let one of you start and go through the southern and western States of this country, and unless you travel as a slave to a white man (a servant is a slave to the man whom he serves) or have your free papers, (which if you are not careful they will get from you) if they do not take you up and put you in jail, and if you cannot give good evidence of your freedom, sell you into eternal slavery.

Radical black abolitionist David Walker proposes this counterfactual journey into the slave states early on in his Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World.1Close In an Atlantic world where freedom had become increasingly territorialized, Walker seizes on travel as an ironic test of the individual freedoms purportedly secured in the federal compact. His series of conditional “ifs” reveal personal liberty to be both racially particularized and geographically bounded. Free blacks—citizens of northern states—either traveled as slaves or risked becoming enslaved upon entry into a slave state. Black movement was permissible only when it was subordinated to white authority. The misnaming of traveling slaves as “servants” or contractual agents with the freedom of choice was a fiction particular to the legal culture of travel and exemplified in the freedom suit. Punitive statutes directed specifically toward curtailing black mobility were common among the states south and west of Mason-Dixon, and they belie the discourse and reality of free travel and free will in a partially free Atlantic world. Free black mariners, whose lives perhaps best typified the cosmopolitanism of Walker’s “coloured citizens of the world,” discovered the dreadful accuracy of his words as they sailed into southern ports. Fearing slave insurrection from within and national interference with slavery from without, South Carolina was the first of the coastal slave states to enact a police law “for the better regulation of Free Negroes and persons of color,” a law that targeted free blacks engaged in the seafaring trade; North Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Louisiana, and Texas soon followed.2Close Officials and harbormasters in these states began seizing and imprisoning, under threat of enslavement, all black sailors once their vessels docked in southern ports.

The Negro Seamen Act (1822) was among a number of “quarantine laws” that guarded the waterways and thoroughfares into South Carolina, as lawmakers sought to delimit the power and potential of black revolutionary consciousness after the unsettling discovery of the 1822 Denmark Vesey plot in Charleston.3Close Vesey, who had supposedly “slaved in St. Domingo, studied with the Moravians, and learned several languages” before his master, a sea captain, resettled him in Charleston, embodied the radical promise of the Black Atlantic.4Close An early instance of what Robert Westley describes as “Black exceptionalism within the law,” the Negro Seamen Act was twice amended by South Carolina to increase its severity.5Close The 1835 amendment subjected black mariners who “ever again enter into the limits of the State” to sale at public auction “as a slave,” with the proceeds divided between the state and informer.6Close Southern states such as South Carolina seized on their sovereign power to decide on the value and nonvalue of life as they effectively deemed certain individuals outside the political community and, therefore, alienable as property.7Close Only two legal identities existed for black sailors under the specific provisions of such police laws: they were either prisoners or slaves. And the prisoner quickly became a slave if jail fees went unpaid. These Negro Seamen Acts made black citizens and foreign nationals, according to Connecticut’s New Englander, “guilty of [the crime of] being free” in southern states.8Close Stripped of any legal means for redress or amelioration, these “mariners, renegades and castaways” of the black Atlantic became slaves of the state in an uncanny continuum between what Orlando Patterson theorizes as the slave’s social death and what Joan Dayan reelaborates as civil death or “dead in law”; these men may possess natural life, but they had lost all civil rights.9Close

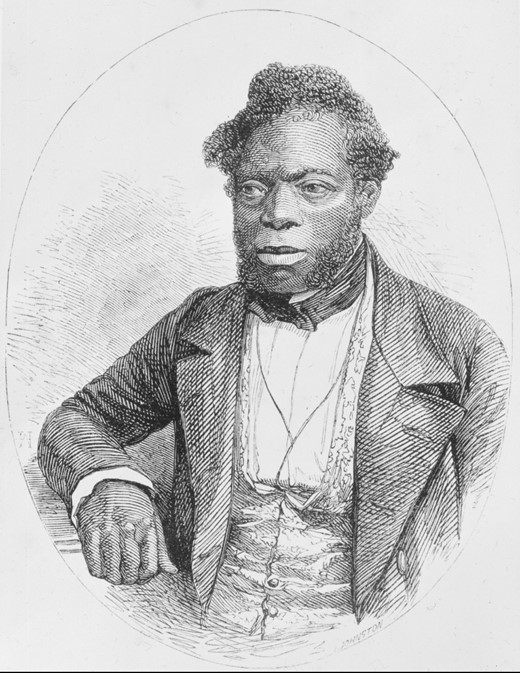

Black Atlantic scholarship has often looked to the chronotope of the seafaring ship in its efforts to limn the cosmopolitan contours of the nineteenth century. Black sailors, according to Jeffrey Bolster, “established a visible presence in every North Atlantic seaport and plantation roadstead between 1740 and 1865” (see figure 4.1).10Close Indeed, Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker regard black maritime circulation as one aspect of the “many-headed hydra” that unsettled political sovereignty along these North Atlantic currents.11Close The “Atlanticist radicalism” of black seafaring life threatened slaveholding localisms in a world where freedom seemed to inch westward, and southern U.S. lawmakers used these fears to further expand state power in relation to the federal government.12Close

Popular British portraitist John Downman (1750–1824) began this black chalk sketch, Thomas Williams, a Sailor (1815), in Liverpool. Williams’s raised hands suggest the supplicating slave posture common in antislavery depictions.

This chapter examines the appeals to law made on behalf of black Atlantic mariners caught up in the workings of these antiblack statutes in coastal slave states. Outraged transatlantic reformers such as F.C. Adams drew public attention to the work of “the State [in] trying to reduce human beings from a state of freedom into that of slavery.”13Close British and American sailors, with the support of their national or state governments, instigated a number of legal actions to challenge the law’s constitutionality and secure its repeal. As the Liberator reported, any of these lawsuits would have tested “before the Supreme Court of the United States the legality of imprisoning such, when color and not crime was the only indictment to be found,” but South Carolina officials blocked all these cases from going before the federal high court.14Close Antislavery activists and opponents of this police regulation increasingly turned to the “bar of public opinion” once they realized that a federal hearing would not be forthcoming and that Congress, controlled by “slavocratic power,” would not act on the issue. Black and white abolitionists and merchants, southern reformers, and free blacks within the Atlantic world forged unexpected alliances as they endeavored to push this issue to the top of the political agenda. In the failure of law, they turned to newsprint, pamphleteering, and literature as they sought to enlist the “public mind” to do the work that legislators and jurists refused to do. These writers and orators, such as Walker, drew forth a revolutionary black consciousness from the law’s negativity and limits, creating an oppositional agenda over these many decades of intermittent transatlantic protest.

The controversial Vesey conspiracy unleashed a public discourse of black revolutionary agency that South Carolina officials and proslavery advocates sought to control for their own political ends, as they drew distinctions between their domestic and foreign black populations.15Close The specter of incendiary blacks foreign to local slaveholding customs justified, in various ways, the necessity of this controversial regulation, as southern ideologues insisted on the “paternal benevolence” of slavery as an institution. Throughout the many decades of public contestation, South Carolina lawmakers periodically reinvigorated this amorphous threat of black foreignness to resolve this rather conspicuous contradiction within slaveholding society: purportedly docile slaves capable of violent insurrection. Officials sought to relocate the threatening revolutionary potential of “domestic” slave populations onto the phantasm of free “foreign negroes.”16Close This racialized regulation of transborder movement also indicates the degree to which U.S. borders were far from open; it offers an early history of the racial exclusions that continued to characterize U.S. geopolitics and the right to free travel well into the twentieth century.17Close Not only did local law thus define the borders of state and nation, but it also, according to Mary Dudziak and Leti Volpp, “delineate[d] the consequence of borders for the peoples within them.”18Close

South Carolina officials sought to transform state aggression against its free black populace into a narrative of white victimization, as the police law activated a powerful sectional doctrine of self-preservation against a “racial” threat constructed as “foreign” to local customs. Public safety, insisted southern lawmakers, necessitated this statute, since “free negroes and persons of color, coming from the North … [had] attempted to corrupt our colored population by instilling into their minds false ideas of their duties and their station, till, by their insidious and exaggerated statements, they succeeded in exciting in the midst of this community a formidable insurrection.”19Close South Carolina advocates insisted on this higher “law of self-preservation” as they marshaled out the language of public health to represent free black sailors as an “infectious disease” capable of overwhelming their domestic slave populations.20Close This history offers one of the starker illustrations of the racial moorings of police power, as lawmakers redefined these free blacks, regardless of national allegiances, into “foreigners” subject to punishment. They became stateless persons as officials stripped them of their legal personhood as either free citizens of northern states or subjects of Western nations. This geopolitical discourse of “foreignness” levied against free black American sailors, in particular, involved a troubling discourse of ontological dislocation and political alienation that was congruent with the slave’s social death.21Close The sailors’ claims on inalienable “native rights” went unheeded.22Close How was black life to be inscribed in the social order given that life or birth in the nation did not necessarily establish black persons as citizens or sovereign subjects? These conflicts over the extension of rights and entitlements to the free black citizens of “sister states,” let alone the subjects of sovereign nations such as Britain or France, further pry apart the modern fiction of the equivalence of nativity and nationality.23Close

Black northerners, concerned about the ongoing violation of their constitutional rights, organized to take action against the Negro Seamen Acts. In 1842, notable black activists including William C. Nell, Benjamin Weeden, and Charles A. Battiste (who also financed a boarding home for black sailors) called a public hearing in Boston to “consider the imprisonment of colored seamen in foreign ports, and to take measures for petitioning Congress and the State Legislature on their behalf.”24Close Such petitions sought to circumvent the Gag Rule that officially suppressed discussion of slavery in Congress from 1836 to 1844. “Several colored seamen,” the Liberator reported of one well-attended meeting, “came forward to testify to the sufferings and cruelties they had experienced in southern prisons.”25Close John Hatfield, a Pennsylvania native and barber aboard a “steamboat plying from New Orleans to Cincinnati,” reported, “[I was] arrested, ironed in the street to degrade me, and put in the jail.”26Close There he found “men from Boston, New York, Baltimore, and other places” who had also been jailed under the Negro Seamen Act, even though they, like Hatfield, “had committed no crime.”27Close Black reformers periodically organized meetings to give “public expression … especially from those the most likely to become victims to the slave code,” and boarding homes for black seamen, such as the one run by black abolitionist William P. Powell, founder of the Manhattan Anti-Slavery Society, became sites for antislavery organizing.28Close

Warned of the dangers of sailing into southern ports, some sailors took matters into their own hands and resisted through desertion or mutiny. Northern senators, for example, reported that “voyages had sometimes been broken up or delayed and embarrassed in consequence of the desertion of colored seamen who had left their vessels on discovering that they were to visit southern ports.”29Close Eighteen black crewmen mutinied aboard the S.L. Bogart in 1857 when they discovered that their vessel was bound for Mobile, Alabama, rather than New York as they had been led to believe. “The alleged cause of the mutiny,” noted the Zion’s Herald, was “the unwillingness of the colored seamen to go where they feared to be reduced to slavery.”30Close Some white captains also joined the fray to defend the rights of their black shipmen. Charles McLean, the British sailing master of the St. Lucia merchant vessel Susan King protested “the cruelty and injustice of such an act” and forcefully repelled the Wilmington harbor officials intent on arresting his black crewmen in 1845.31Close

Stories of free black seamen thus imprisoned and sold into slavery through the cupidity of unscrupulous captains and southern police officers became a common feature of the antislavery platform and print culture.32Close In 1834, the Committee on the Domestic Slave Trade of the United States emphatically reported, “There is a continual stream of free colored persons from Boston, New-York, Philadelphia, and other seaports of the United States, passing through the calaboose into slavery in the country.”33Close This report described in detail a number of cases of kidnapping, in which avaricious captains took advantage of the Negro Seamen Acts to profit from the enslavement of their free black crewmen. The experience of Boston seaman Robert Roberts—who was “kidnapped at New Orleans, and committed to the calaboose, preparatory to being sold and sent into the interior”—illustrates the utter precariousness of black freedom across the border separating free from slave state.34Close Roberts suspected “that his captain, a Scotchman named Bulkley, was privy to the outrage,” and he narrowly escaped enslavement, in a telling instance of the cosmopolitanism of black seafaring life, for if he had not “been able to speak French” to the “creole French soldier who was on guard”—whom he convinced to deliver a message “to two friends in the city, who obtained his release”—he would have been sold.35Close Roberts shared his New Orleans prison quarters with “nine colored men, whom he knew to be free, having known several of them as stewards on board northern vessels. Two of them belonged to Boston, one to Portland, and three to New-York. After twenty days, they were to be sold.”36Close Other shipmasters exploited their crewmembers’ fears of enslavement to coerce them into signing disadvantageous contracts, until sailors successfully challenged this practice before Massachusetts court in Stratton et al. v. Babbage (1855).37Close

Few statistics exist for the number of sailors incarcerated and sold as slaves in southern states, yet a keeper of a “Seaman’s Home” in New York estimated that twelve hundred black sailors were seized annually in New Orleans, five hundred in Charleston and three hundred in Savannah.38Close London’s Anti-Slavery Reporter likewise reported, “upon the very best authority, that in 1851, thirty-seven British subjects were seized and incarcerated, and forty-two in the course of last year; and that there is no doubt of many free coloured British subjects having been sold into slavery under the operation of this law, all traces of whom have been lost.”39Close When the South Carolina Assembly finally deliberated the modification of its law in 1856, “[i]t was shewn,” according to the Anti-Slavery Reporter, “that no less than seven hundred and thirty coloured seamen, for no crime whatever, were incarcerated in the Charleston prison during the short span of ten months.”40Close

American abolitionists opposed to the South Carolina law stressed unrestricted interstate travel as an essential right of citizenship to counter these proliferating regulations against black American seamen in southern ports. Indeed, Congress had long recognized the exceptional status of mariners in 1796 when it passed “An Act for the relief and protection of American Seamen” authorizing seamen protection certificates to black and white merchant seamen certifying their status as national citizens to protect them from impressment.41Close The popular conception of the constitutional right to “free travel” (discussed further in the conclusion) forced the government to reckon with the place of free blacks within the nation. What did legal freedom mean if police laws such as South Carolina’s Negro Seamen Act disregarded the rights accorded to the free? Both American and British antislavery activists pondered this question. The various accounts of “kidnapped” free black sailors offered a powerful cautionary tale of postemancipation freedom. Memorials, lectures, novels, and pamphlets protesting these police laws repeatedly stressed the Atlantic contours of an antislavery campaign that transcended both national identifications and geopolitical boundaries. The uneasy and shifting alliances of abolitionists, sailors, reformers, and commercially affected merchants brought international attention to bear on the far-reaching effects of slavery in the United States. The British government insisted that the South Carolina statute violated the 1815 treaty providing for the “reciprocal liberty of commerce” between the two nations, and concerned Americans protested it for violating citizenship rights and interstate comity. Critics couched their protests within the legal paradigm most legible to the federal government: the constitutional privileges and immunities pledged to citizens as “agents of contractual liberty.”42Close These overlapping protests challenged the United States to define itself as either a nation among a community of nations or a confederation of sovereign states.43Close

Outcries against the Negro Seamen Act ignited congressional debates over whether the individual states or the federal government possessed the authority to regulate travel or “free ingress and regress” across state lines. Massachusetts senator Robert Charles Winthrop, who also led the northern opposition to the proposed Fugitive Slave Bill, cited the Negro Seamen Acts as instances of southern noncompliance with interstate comity and the privileges and immunities of state citizenship secured in the Constitution.44Close Well in advance of the denationalization of black citizenship in Dred Scott v. Sandford, South Carolina’s “extraordinary law” deemed free blacks not citizens of the United States within the meaning of the Constitution, instituting racial classifications instead as the basis for political entitlement.45Close Antislavery newspapers noted the complex political relays between the plight of fugitive slaves in the North and black sailors in the South, caustically attacking lawmakers “in favor of aiding in the capture of Fugitive Slaves” but “dumb in regard to the arrest and imprisonment of free colored seamen at the South.”46Close A public discourse defining this constitutional right to free interstate travel emerged out of these protests against the Negro Seamen Act. The “right of free entrance into any of the states of the Union,” urged northern advocates, “is the very first among the privileges of citizens.”47Close Connecticut’s New Englander, for example, insisted over three lengthy treatises in 1845 and 1846 that these black citizens of northern states simply exercised their right to “free ingress and regress,” concluding that South Carolina’s regulation violated this constitutional guarantee of reciprocal travel privileges.48Close

As sectional passions intensified, the South Carolina Assembly enacted additional measures that suspended habeas corpus, generally acknowledged as fundamental to citizenship, for all free blacks entering the state. The amended Negro Seamen Act of 1844 stipulated that “no negro or free person of color, who shall enter this State on board any vessel … and who shall be apprehended and confined by any sheriff in pursuance of the provisions of said act shall be entitled to the writ of habeas corpus.”49Close This measure was significant given the longstanding role of habeas corpus in Anglo-American jurisprudence and political philosophy as “an instrument of individual freedom against arbitrary imprisonment” by the state and especially given the writ’s centrality to the history of Anglo-American antislavery activism since Somerset.50Close “The doors of the courts of justice,” observed a Massachusetts statesman, “are effectually closed, and apparently closed forever” to such sailors.51Close Black sailors were thus made “dead in law,” possessing natural life but stripped of civil rights.52Close These legislative enactments appalled Douglass’s North Star, which deemed them a “revolting injustice” in a “country and under a Government boasting of its Freedom, its Civilization and its Justice!”53Close

An individual who invoked habeas corpus asserted the right to be subject to the law rather than to arbitrary power; the revised Negro Seamen Act specifically prevented incarcerated black sailors from seeking reprieve through legal channels.54Close The “law is his enemy,” announced the New Englander, “[i]f crossing the line of his native state, he is detained, by whatever necessity, beyond the short period of absence which the law may allow.”55Close These excessive measures outraged newspapers such as the New York Daily-Times, which condemned the power invested in local sheriffs “to seize the unfortunate black freeman, convey him as a felon through the public streets, incarcerate him in the common jail, and release him only at the period, no matter how remote, of the sailing of the vessel to which he had been attached.”56Close Few full accounts of the seizure, imprisonment, and auction of free black seamen exist within the historical record, precisely because these seamen were barred from appealing to courts for arbitration. The following sections critically reconstruct a number of these cases to read them alongside material from the Anti-Slavery Recorder, John Brown’s slave narrative, David Walker’s antislavery jeremiad, Samuel Ringgold Ward’s British oratories, and the largely unexamined antislavery writings of F.C. Adams, specifically the novel Manuel Pereira. As these cases starkly exposed the limits of the law in a partially free Atlantic world, black and white abolitionists turned to literary and rhetorical appeals in their decades-long transatlantic struggle to reshape South Carolina’s racial jurisprudence.

Preserving State Sovereignty

The Negro finds himself an unprotected foreigner in his own home.

—Sutton E. Griggs, Imperium in Imperio, 1899

Conspiracies such as Denmark Vesey’s Charleston plot were undoubtedly flashpoints in the complex history of black resistance to slavery and its racial ideologies, yet the slave state also enlisted the potential of black revolt in the centralization of its power.57Close The trope of black revolt, notes Maggie Sale, was often “a site of contestation among unequally empowered groups.”58Close Southern lawmakers marshaled the threat of black revolt as the groundwork for the exercise of police power.59Close The imagined dangers of “free foreign negroes” thus became the basis of a powerful racial jurisprudence that restricted individual rights in the name of “self-preservation.” Indeed, Kent’s Commentaries on American Law observed that the “great principle of self-preservation doubtless demands, on the part of the white population dwelling in the midst of such combustible materials, unceasing vigilance and firmness.”60Close These ubiquitous Negro Seamen Acts sought, in Eric Sundquist’s terms, the “countersubversive containment of revolutionary energy,” yet southern lawmakers found themselves reinvigorating the revolutionary potential forestalled in Vesey’s conspiracy in order to secure popular consensus for periodic expansions to the law.61Close South Carolina statesman and jurist Benjamin Faneuil Hunt, for example, defended the South Carolina act in Ex parte Henry Elkison v. Francis G. Deliesseline (1823), one of the earliest cases to challenge the police regulation, with an alarmist vision of the state convulsed in the throes of a mass slave uprising: “If South-Carolina has to dread the moral pestilence which a free intercourse with foreign negroes will produce, she has, by the primary law of nature, a right within her own limits to use every means to interdict it—she is not bound to wait until her citizens behold their habitations in flames.”62Close Lawmakers uncoupled black revolt from actual historical events and transformed it into a free-floating phantasm to authorize the continual expansion of police power against their black and white populations.

Black mariners sailing under the protection of Western nations such as Great Britain and France were also subject to this police law as coastal slave states acknowledged, in a negative fashion, the revolutionary possibilities of a black Atlantic reshaped by the Haitian Revolution and West Indian Emancipation. The Richmond Enquirer, for example, angrily justified South Carolina lawmakers: “Are they bound to receive aliens, who may carry the very seeds of insurrection into their bosom? Suppose our slaves returning from Hayti,—suppose suspected tools from that island should arrive in Charleston in a British vessel,—is there no right to guard against the danger?”63Close Proslavery lawmakers often invoked the specter of San Domingo’s successful slave revolt to defend regulations against black sailors as necessary policing measures. In the beleaguered 1845 congressional debate over the admission of Iowa and Florida, Mississippi senator Robert Walker defended a similar prohibition in the Florida constitution as the only guarantee against the entry of “[f]ree colored seamen [who] were dangerous to a slaveholding community,” including “runaway slaves from St. Domingo, who had been concerned in all the atrocities perpetrated there, and whose hands had been imbrued in the blood of their masters.”64Close This slave revolution found localized intensifications in Nat Turner’s uprising and the averted conspiracies of Gabriel Prosser and Denmark Vesey. Indeed, these compounded memories of black revolution persisted with vivid and unabated force within the political discourses of southern jurisprudence at midcentury. These historic slave conspiracies undoubtedly contributed to the fear of revolt, but southern lawmakers also actively reshaped the public memory of these events to serve their political interests.

South Carolina governor William Aiken, Jr., for example, offered a revisionist legislative history that cast the state’s domestic tranquility as dangerously undermined by the combined corrosive forces of “foreign free persons of color” and abolitionist “fanaticism.” South Carolina’s native slave population, Aiken suggested, was vulnerable to the “seduction” of “foreign free persons of color”; the Negro Seamen Act was a “humane” measure to “protect” both the “slave and master.” The historic events of Vesey’s plot had become, in Aiken’s words, “the most irrefragable evidence” for the continued necessity of South Carolina’s policy against these dangerous foreigners:

In 1822, a most dangerous and extensive conspiracy of the black population in and about Charleston, was discovered. It had been chiefly planned and devised by foreign free persons of color, who had seduced and corrupted the native free blacks and slaves…. The trial of the culprits elicited the most irrefragable evidence of their active agency, and of the dangers arising from the intermingling of foreign blacks with our slaves, and humanity demanded, both for the slave and the master, that they should be protected from these seductions.65Close

In studied contrast to the apocryphal warning that Charleston Times editor Edwin Holland sounded in the wake of the Vesey conspiracy—“Let it never be forgotten that, the ‘our negroes are truly the Jacobins of the country; that they are the anarchists and the domestic enemy”—Aiken’s revisionist history transferred this danger posed by “our slaves” to the spectral figures of “foreign free persons of color.”66Close Foreignness defined the racial boundaries of a kind of liminal inclusion for those “native free blacks and slaves” who existed within the imagined social order of the slave state. Aiken’s “appeal to history,” as the New Englander observed, sought, among other things, to locate insurrectionary desire for freedom in an external “foreign” population, even though the trial testimony of suspects named in the Vesey conspiracy tended to “prove that this, like all other attempts of this kind, sprung from internal causes.”67Close Rather than acknowledge the “domestic” origins of slave unrest, southern legislators and officials had begun to represent “the rank and file of the conspiracy as the victims of foreign seduction” in the concerted effort to redirect the source of revolutionary black agency elsewhere beyond the boundaries of the state. This discourse of seduction paralleled the fantasies of individual slaveholders such as Samuel Tredwell Sawyer, who remained convinced that John S. Jacobs would return to him, reimagining the escape of their slaves as the work of meddlesome white abolitionists who had “decoyed” them away. “Southern imagination, unrestrained by the literal record,” proclaimed the New Englander, had become the unlikely rationale for the enactment of those “obnoxious laws” under which free black northern citizens suffered without access to any legal means of redress.68Close

The South Carolina law quickly became, in the words of the Southern Quarterly Review, the gravest question to agitate the Union “since the formation of the government,” hastening sectional divisions and plunging the nation into international conflicts with Great Britain and France.69Close Police officials began to seize and incarcerate all free black seamen found aboard vessels arriving into Charleston Harbor once the law went into effect in 1823. Not a single crewmember was left aboard a British vessel in one “remarkable” case.70Close These actions immediately ignited protests from affected French, British, and American sailors and shipmasters, who appealed to their national and state governments for relief. France first petitioned the U.S. government in 1837, and the minister of marine on numerous occasions issued circulars to French shipmasters warning them of these Negro Seamen Acts.71Close

The case of Jamaica-born free black Henry Elkison was the first of many unsuccessful British lawsuits to test the South Carolina Negro Seamen Act. Stratford Canning, the British minister in Washington, secured an early pledge from Secretary of State John Quincy Adams that British seamen would not be seized in Charleston Harbor. The British consul brought charges against the Charleston sheriff, Francis Deliesseline, and petitioned U.S. Supreme Court Justice William Johnson, a Charleston native, for a writ of habeas corpus to release Elkison after authorities, at the urging of the South Carolina Association—an extralegal organization of private citizens (many of whom were Charleston public officials)—arrested him off the Liverpool merchant vessel Homer.72Close Johnson heard Ex parte Henry Elkison v. Francis G. Deliesseline (1823) while riding circuit, and his ruling, which dismissed the habeas request on procedural grounds, proffered perhaps one of the more controversial instances of judicial dictum until Taney’s Dred Scott opinion.73Close

Before a crowded summer courtroom, Justice Johnson ceded authority to the slave state in the case, even though he admitted, in what was tantamount to a declaration of the law’s inherent lawlessness, that Elkison’s “right to his liberty” without “remedy to obtain it” was an “obvious mockery” of law.74Close Habeas corpus jurisdiction only extended to persons held under U.S. authority, and Elkison, as Johnson acknowledged, was confined “arbitrarily and without authority by a state officer, a case to which our power to issue this writ does not extend.”75Close Indeed, these sailors, in F.C. Adams’s evocative imagery, were thus “held by the thumb-screws of law.”76Close Johnson denounced the Seamen Act as a violation of both the enumerated congressional power to regulate commerce with foreign nations and the 1815 treaty with Great Britain establishing “reciprocal liberty of commerce” and the “right of navigating their ships in their own way.”77Close Even though such criticisms were mere dicta without binding legal power once Johnson professed his lack of jurisdiction, some antislavery newspapers misreported them as cause for celebration.78Close In response, the Charleston Mercury rather smugly announced “that the act of the South Carolina Legislature, so far from being suspended, since the trial of Elkison, proceeds in operation more rigorously, perhaps, than before.”79Close Regional papers ranging from the Baltimore Patriot & Mercantile Advertiser to Maine’s Eastern Argus likewise noted “that, from the continued arrivals of free persons of color at that port, the people of the north have been led into an error by the publication of Judge Johnson’s opinion.”80Close Indeed, Johnson gave federal sanction (albeit grudgingly) to the legality of the South Carolina act: like later U.S. officials beleaguered by similar petitions, he possessed, in his words, “no power to issue the writ of Habeas Corpus” and referred Elkison’s consul to the South Carolina government.81Close

Elkison’s case, as reported in Britain, brought pressure to bear on the uncertain status of blacks in a nation still internally divided over the question of immediate or gradual abolition in the West Indies. The British Christian Register, for example, remarked on the striking “resemblance of the American slave logic to the similar argumentation of our West Indian Man-owners.”82Close Indeed, the southern “tirade” in Elkison, this British periodical continued, “resembles many of the West Indian flights on the same subject,” including declarations of “the rights of property, separation from Great Britain.”83Close Reportage of Elkison’s case in the United States also deepened the rift between the free and slave states. Johnson’s pronouncements in Elkison, needless to say, were highly unpopular in the South, and many southerners eagerly echoed South Carolina Association solicitor Isaac E. Holmes’s strident letter to the Charleston Mercury: “if South Carolina was deprived of the right of regulating her colored population—it required not the spirit of prophesy to foretell the result, and that, rather than submit to the destruction of the state, I would prefer the dissolution of the union.”84Close Holmes’s antiunionist words anticipated the tenor of the “nullification crises” that pitted South Carolina against President Andrew Jackson over the federal tariff acts of 1828 and 1832.85Close Charleston newspapers, fearing riots, deemed it “inexpedient to publish … Judge Johnson’s Opinion,” but Niles’ Weekly Register published the complete transcript of Johnson’s opinion in September, and editorialized versions of the case soon began appearing in northern newspapers.86Close Johnson’s opinion and the arguments of Benjamin Faneuil Hunt, whom the South Carolina Assembly had engaged to defend Sheriff Deliesseline, were published later that year in Charleston as the pamphlet The Argument of Benj. Faneuil Hunt, in the Case of the Arrest of the Person Claiming to Be a British Seaman.87Close

Hunt, an ardent unionist, voiced many of the key arguments that the state used to defend its police laws against “foreign negroes,” affirming the state’s right to use a range of force that at first restricted and then revoked the personal liberties of black citizens and foreign nationals alike. Classic theories of state formation hold that “modernity begins when government claims a monopoly on legitimate violence within its territory,” and, as John Torpey contends, modern states seized, in a parallel action, the authority to regulate movement and to identify “unambiguously who belongs and who does not—in order to ‘embrace’ their members more effectively and to exclude unwanted intruders.”88Close In this vein, Hunt drew largely from Swiss legal philosopher Emmerich de Vattel’s Law of Nations (1758) to argue that South Carolina merely exercised its right as a sovereign state to “interdict altogether the entry of foreigners into his dominions.”89Close This right to control entry was an essential feature of state sovereignty, which Hunt likened to the patriarchal imperium:

the civilized man can secure his family against the contagion of the dissolute or depraved, by closing his doors, or selecting his visitors;—So, every sovereign state, has the perfect right of interdicting all intercourse with strangers, or of selecting those whose influence or example she may fear, and confining the exclusion to them. A master of a family receives or excludes his visitors, according to the peculiar situation and feelings of his own household. A State must be the sole judge to decide what strangers may or may not enter. The power to exclude or to admit strangers, implies the right to direct the terms upon which those who are admitted shall remain. As an individual may direct what apartment his guest shall occupy, a state may confine strangers to such limits, as its own policy may dictate.90Close

Hunt implicitly evokes a Federalist understanding of imperium in imperio, or “sovereignty within sovereignty” (the division of power within one jurisdiction), to argue that the state, when acting in the service of protecting its populace from harm (like the patriarch over his household), should not be subject to constitutional scrutiny.91Close

The regime of police laws that Hunt defends and likens to the patriarchal imperium increasingly restricted what constituted acceptable forms of social relations. The “preservation” and “defense” of such slaveholding customs required the continual reinforcement of police power against free blacks.92Close The regulation of free “foreign negroes” was vital to the so-called moral health of the slave population. “This State,” as Hunt explains, “having a large slave population, conceives it prudent to guard against the moral contagion which the intercourse with foreign negroes produces, and therefore she prohibits them from remaining in any other part of the State.”93Close Free blacks, by definition, were threats to a slaveholding society founded on violently enforced racial dichotomies between slave and citizen, foreigner and native, black and white. In thus “monopolizing the legitimate means of movement,” to borrow Torpey’s words, the slave state further established its identity in the process of excluding and thereby distinguishing foreigners and aliens from its native populace.94Close Hunt’s strategic and repeated use of the term “foreign negroes” constructs black Americans who were citizens of sister states as outsiders to their own nation. What did it mean to be a citizen in a northern state but not have the “privileges and immunities” of citizenship once in a southern jurisdiction? Whereas antislavery periodicals like the Liberator distinguished “foreign seamen” from “native American seamen,” advocates of the South Carolina regulation effectively redefined all black sailors as “foreigners.”

This doctrine of self-preservation and states’ rights was the cornerstone of the southern defense of its increasingly punitive Negro Seamen Acts. When the British consul in Charleston again protested the imprisonment of free black seamen, the Charleston Mercury argued that this law “has its foundation in the right of every organized society to protect itself,—a right which no Government can be expected to surrender.”95Close The state’s sovereign right to self-protection cannot be compromised for the sake of respecting the civil liberties of a few foreign nationals: “The safety of a whole State must be consulted, although it results in temporary inconvenience and annoyance to a coloured or even a white British seaman.”96Close Governor John Means, facing one of the more concerted diplomatic assaults on the law in 1852, stressed with hyperbolic certainty, as did nearly every other South Carolinian before him, that “the right of self-preservation … [is] a right which is above all constitutions, and above all laws, and one which never was, nor never will be, abandoned by a people who are worthy to be free” (MP, 356; emphasis added). In defending the necessity of the Seamen Act, Means invokes a natural right (of self-preservation) that exists outside or “above” the existing legal order. This law is paradoxically enacted precisely to deal with this “extralegal” situation. Such contradictions within South Carolina’s governmentality illustrate powerfully what Giorgio Agamben describes as the “state of exception”: no system of law is fully complete unto itself but relies upon an “exception”—a suspension of the norm—that exists both within and outside the juridical order that it helps constitute.97Close The South Carolinian defense of the Negro Seamen Act, its law that becomes a “right which is … above all laws,” thus reveals the necessary incoherence of the slave state in relation to the law.

Sectional Crisis and the Denationalization of Black Citizenship

Throughout the antebellum period, Great Britain continued to demand “redress and reparation” for the arrest and confinement of its black mariners in the United States, and it lodged eight more petitions with the U.S. government for such “violent and unjustifiable act[s]” and “outrage[s].”98Close Within a year of Elkison, the British minister Henry Addington brought the Marmion case before President James Monroe, seeking the repeal of South Carolina’s “very grievous law.”99Close The Marmion, according to its captain, Peter Petrie, “was not well moored at the wharf, before the officers, who were appointed to put this law into execution, came on board, and forcibly carried one of the four of these men to jail, where he remained during my stay in Charleston.” Three other black crewmen whom Petrie had safely transferred onto a New York bound packet were, according to his testimony, “apprehended by men who seemed anxious only to get their fees, and thrown into prison, depriving them of the opportunity to comply with the law, which they would have done in a few hours.”100Close Charleston police, however, continued to enforce its law against black British mariners despite the inquiries of successive U.S. secretaries of state, especially after the discovery of David Walker’s incendiary Appeal circulating among Charleston slaves in early 1830.

South Carolina reacted violently to the discovery of Walker’s Appeal and rejected these diplomatic appeals to suspend the operation of its police law against black British subjects. British Foreign Minister to the U.S. Charles Vaughan called on Secretary of State Martin Van Buren to intervene on behalf of yet another black Briton, a cook named Daniel Fraser, who was seized from his Liverpool merchant vessel, the Atlantic.101Close Vaughan’s formal remonstrance sought to impress on Van Buren “how hopeless it is to expect that the magistrates of Charleston will set at liberty Daniel Fraser, or to look forward with any confidence to the repeal of the obnoxious act by the legislature of the State.”102Close Indeed, the circulation of Walker’s pamphlet coincided with a marked change in national policy toward these state police laws. In 1831, after recent protests against the Negro Seamen Acts, Attorney General John Berrien overruled former Attorney General William Wirt to declare, according to Fehrenbacher, that “state police powers protected in the Tenth Amendment took precedence over federal power to regulate commerce.”103Close

British diplomatic protests against South Carolina again erupted in 1843 over the seizure and incarceration of a black steward from the British vessel Higginson. Police officers physically assaulted and committed the steward to solitary confinement after he refused to labor for them. Coerced labor was not uncommon among imprisoned sailors. “The law,” as the Charleston Courier observed, “does not define the power of jailors over the persons confined under its provisions, and had provided no efficient means of securing to them comfortable quarters and protection from tyranny and cruelty.”104Close George Tolliver, a free black American sailor who had been incarcerated on seven different occasions reported that “when thus imprisoned, he was denied a sufficiency of food, and compelled to perform various menial and disgusting offices in the prison; though … the captain was obliged to pay a full, if not an exorbitant price for his board.”105Close Undermining the distinction between the free and enslaved, the unwaged labor coerced from these incarcerated sailors anticipated the one exception to the legislated abolition of slavery reinstated in the Thirteenth Amendment, which permitted “involuntary servitude for those convicted of crimes.”

The British were not alone in their demands for the repeal of “the obnoxious law.” Massachusetts Whig Journal editor David Child’s address before the New England Anti-Slavery Society noted, “Forty respectable master[s] of American vessels lying in the port of Charleston, whose men had been seized and were then in prison, petitioned Congress for redress in 1823.”106Close Led by Captain Jared Bunce of the Georgia, a regular trader between Philadelphia and Charleston, the petitioners urged the federal government to “adopt such energetic measures as will relieve … their free colored mariners … [from] an unlawful imprisonment, and their vessels … [from] an enormous and unnecessary expense and detention.” Bunce had appealed “to a court of the state of South Carolina for a habeas corpus, to inquire into the cause of the arrest and detention of Andrew Fletcher, (steward), and David Ayres, (cook), both free colored persons, and native citizens of the United States.”107Close The case eventually came before the South Carolina Supreme Court, where “the case was suspended, and the prisoners were deprived of the relief for which they moved; and do still remain in confinement.”108Close Indeed, the South Carolina Supreme Court employed this tactic with similar results in the case of Portuguese sailor Manuel Pereira, examined at length later in this chapter. Bunce’s congressional petition, like his stalled court case, “appear[s] to have been disposed of among a mass of matters,” even though “[c]itizens of free states, Maine, New-Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode-Island, Connecticut, New-York, and Pennsylvania” continue to be “seized and sold into bondage.”109Close

In Massachusetts, a state historically identified with both maritime commerce and abolitionism, mercantile interests and antislavery “radicals” found a peculiar and uneasy alliance in their united protests against the Negro Seamen Acts. Petitions protesting the seizure and imprisonment of black mariners were repeatedly brought before the state legislature. Massachusetts lawmakers were sympathetic to the plight of shipmasters and crewmen, yet they carefully couched their protests in terms of commerce and constitutional right while avoiding arguments that might be misconstrued as endorsing abolitionism. The Massachusetts legislature revisited the issue in 1839, when it appointed a Special Joint Committee “to inquiry into the expediency of providing for the deliverance of citizens of this Commonwealth, who may be imprisoned and liable to be sold as slaves.”110Close The committee’s minority report catalogued the recent outrages against free black northern citizens with a number of affidavits from “colored citizens of New Bedford … who have suffered under the laws in question.”111Close John Cory, “a free born citizen of Massachusetts, a native of the town of Westport,” reported that “a couple of persons, calling themselves officers, came on board” and seized him off the trading sloop Rodman in 1824. “[S]even others, colored like myself, were in prison,” according to Cory, even though “[n]o offence was charged upon any of us.” The Charleston police dealt similarly with Richard Johnson, the wealthy black merchant who underwrote the Rodman’s commercial voyage south. The report concluded “that facts of this kind may be obtained from the captain of every northern vessel, that has visited Charleston with colored persons on board.”112Close

In the 1840s, public protest over the imprisonment of northern seamen in Charleston crystallized into a specifically regionalized dispute between Massachusetts and South Carolina that further aggravated sectional feelings throughout the nation. South Carolina’s stubborn refusal to modify its law may be explained, as Guyora Binder argues, “as a dialectical moment in its controversy with the North over slavery itself,” which simultaneously forced free states such as Massachusetts to solidify their liberal ideologies.113CloseMassachusetts and South Carolina each responded to the issue of slavery through the extreme territorializing of its state power. South Carolina admitted the right of Massachusetts “to elevate the descendants of the African race to the rank or status of free white persons … within her own limits” but vigorously denied “that she has any right to require us to extend to such of them as may enter our limits.”114Close Advocates of South Carolina argued that southerners often had “on board their own vessels, colored seamen who were slaves. If one of these vessels went into a port of the state of Massachusetts all those slaves were instantly emancipated.”115Close Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw of the Massachusetts Supreme Court had indeed begun in 1844 to free slaves brought into the state on board ships, in Commonwealth v. Potterfield and Commonwealth v. Fitzgerald. Coastal slave states persisted in arresting black sailors who arrived on their shores, just as free states led by Massachusetts began to free, by writ of habeas corpus, those slaves who were brought within their bounds by traveling slaveholders.

These Negro Seamen Acts made it impossible for abolitionists to address the problem of slavery without attending to the condition of free blacks within the American polity. Abolitionists insisted that these “severe penal restrictions” were an outgrowth of “that cursed system of murder, robbery, adultery, and every other sin under heaven, called American slavery,” even as merchants, British diplomats, and state legislators continued to couch their protests in far less politicized terms.116Close The Massachusetts legislature, for example, authorized the governor to appoint agents in Charleston and New Orleans “for the purpose of collecting and transmitting accurate information respecting the number and the names of citizens of Massachusetts, who have heretofore been or may be … imprisoned without the allegation of any crime.”117Close The Charleston appointment was initially extended to Benjamin F. Hunt, the same man who passionately defended South Carolina law in Elkison, in the effort to distance this resolution from the divisive “question of abolition.”118Close This desire to dissociate protest against South Carolina’s Negro Seamen Act from abolitionist politics was not unusual. The American Colonization Society’s African Repository, for example, protested in sympathy with “respectable” ship owners who were forced to suffer economic hardships, but it remained firmly set against “the question of abolition.”119Close

Sectional feelings reached a tipping point when, in 1844, the newly elected Massachusetts governor, George N. Briggs, commissioned Samuel Hoar as his representative to Charleston and Henry Hubbard to New Orleans, directing the two to prosecute lawsuits on behalf of Massachusetts citizens at the expense of the public treasury. A lawyer specializing in maritime law, Hoar would have brought a civil suit before the U.S. Supreme Court to test the constitutionality of the Negro Seamen Act.120Close However, the South Carolina legislature, once notified of Hoar’s appointment, condemned his mission and issued a nearly unanimous series of resolutions authorizing Governor William Aiken, Jr., to expel him as an “emissary of a Foreign Government, hostile to our Democratic Institutions, and with the sole purpose of subverting our internal police.”121Close It furthermore declared that “free negroes and persons of color are not citizens of the United States, within the meaning of the Constitution, which confers upon the citizens of one state the privileges and immunities of citizens of the several States.”122Close This denationalization of black citizenship closely echoed the statements of former Attorney General Roger B. Taney, as he tried to forestall British diplomatic efforts to redeem sailors seized under North Carolina’s Negro Seamen Act, statements that Taney later developed in his Dred Scott opinion: “The African race in the United States even when free, are everywhere a degraded class, and exercises no political influence.”123Close The South Carolina attorney general, fearing the national condemnation that would be levied on the state if Hoar should be lynched, charged the Charleston sheriff to escort him from the city.124Close

Garrison’s Liberator seized on Hoar’s banishment as an opportunity to consolidate public opinion against “slaveholding power,” condemning it as tantamount to South Carolina’s extraordinary rejection of a white citizen’s constitutional right to unmolested free travel.125Close The excessive measures taken against Hoar offered the antislavery weekly a “fresh confirmation of the hideous fact, that no man who is suspected of being an abolitionist can travel in any slaveholding state, without endangering his property, his liberty, or his life!”126Close Stunned by South Carolina’s excessive measures, many newspapers saw Hoar’s expulsion as a “gross insult” to a sister state in defense of an “outrageous law.”127Close Hoar’s expulsion as an “enemy” of the state did seem to be a grave misstep in South Carolinian statecraft, diplomacy, and public relations, and a number of concerned commentators saw the escalating conflicts between the two states as further “weaken[ing] the bonds which unite the different sections of the confederacy.”128Close To some northerners, these actions were all the more galling because they had been taken against a “free white citizen of Massachusetts,” and the Liberator cautioned against this slippery slope of restrictions on interstate travel: “The insatiable appetite of the slave power is no longer satisfied with black victims,” and “the jails of the South are fast filling up with victims from the ranks of the whites—the educated and refined—the old colony stock of ancient Puritan blood!”129Close Many northerners were apoplectic over this refusal to grant the venerable statesman his “privilege of locomotion, under the American Constitution!”130Close “The sovereignty and dignity of the State of Massachusetts,” as other partisan papers reported, “were represented by Mr. Hoar…. Massachusetts herself appeared in his person … and it is Massachusetts, in the person of Mr. Hoar, that is expelled from South Carolina.”131Close

The uncivil treatment of black and white northern citizens angered many people, who argued that South Carolina did not offer the “same degree of protection” to American citizens as it did to “those of foreign powers” such as Britain and France.132Close Sectional rhetoric often accompanied such critiques of this preferential treatment of black Britons. Such references to the “foreign” gave a nationalistic edge to the discourse of U.S. sectionalism, especially given the fact that these claims were patently untrue. Charleston officials continued to seize and imprison black Britons, even though American antislavery activists often claimed otherwise. American antislavery print culture thus appropriated the proslavery discourse of “foreign negroes”: “foreigners” became opposed to American “countrymen” in editorials deriding southern discrimination against “citizens of the free States of the Union.”133Close Abolitionist campaigns for the repeal of these Negro Seamen Acts were thereby articulated with U.S. nation-building projects that sought to secure the boundaries of national identity. John Palfrey’s Papers on the Slave Power (1846), for example, hyperbolically reported that “the British Lion … gave a growl and snap, and the Carolina people presently found out that it was perfectly safe to let British blacks come and go without hindrance or harm, even though they should be lately emancipated slaves from Barbadoes or Jamaica; while they cannot see to this day that it is at all safe to take the same course with blacks from Massachusetts.”134Close Such references to the South’s preferential treatment of British over American seamen sought to enlist nationalist loyalties and identifications in the antislavery campaign to repeal the Negro Seamen Acts, even as these activists eagerly sought to rally transatlantic support for their efforts. As U.S. sectional tensions flared in the 1850s, British abolitionists, in an analogous gesture, denounced American aggression against British civil liberties in their efforts to rouse public opinion against slavery and to further identify freedom with British law and cultural heritage.

The Afterlife of Manuel Pereira in the Transatlantic Antislavery Campaign

The people of Charleston might now inquire why they have so much law and so little justice?

—F. C. Adams, Manuel Pereira; or, The Sovereign Rule of South Carolina, 1853

A new spate of transatlantic disputes over the incarceration of black British seamen erupted in the early 1850s, as Great Britain, pressed by an outraged public, increased its diplomatic efforts to secure the repeal of the South Carolina Negro Seamen Act. This section charts this final decade of popular mobilizations to repeal the regulation, as three cases in quick succession captivated the British public. Abolitionists challenged Britain’s commitment to protecting the rights of its newly emancipated black subjects. A number of editorials surfaced in the London Times expressing the public condemnation of what was viewed as an arbitrary law of racial exclusion that was a violation of British rights and an affront to the nation. One letter, addressed to Lord Palmerston, offered an eyewitness account of the routine workings of “white law” in Charleston: “I was in America in 1839 and 1840, and remember very clearly that the entire black crew of a ship from St. Domingo, captain, able hands, and all, were packed into prison during the whole time the vessel remained in the same port of Charleston, South Carolina.”135Close The British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society regularly devoted columns of its monthly publication, the Anti-Slavery Reporter, to the “Imprisonment of Coloured Seamen” as it informed the British public of the depredations perpetrated on its free black subjects. It offered ample coverage of the Parliamentary deliberations over the case of sailor Manuel Pereira, who had become something of a cause célèbre, alongside moving narrative accounts of British seamen seized and sold into slavery. Anglo-American abolitionists sought less to address the abstract points of law than to guide public sympathy toward the harrowing plight of black mariners in southern ports.

The Anti-Slavery Reporter was one of the earliest newspapers to report on the seizures of Isaac Bowers and Rueben Roberts, calling on “the British press and public to demand from Government immediate measures to prevent future outrages of this kind” and insisting that it “must receive a definitive answer, whether the colored population belonging to this country and its various dependencies are to be treated as felons and slaves in any ports of the United States.”136Close Great Britain’s concerted efforts in the 1850s to dispute South Carolina’s Negro Seamen Act brought international scrutiny to bear on the questions both of federal powers and of institutional slavery in the United States. Britain’s refusal to indemnify U.S. slaveholders for slaves set free from distressed or wrecked American vessels in the British West Indies did not contribute to amicable foreign relations. In 1841, Secretary of State Daniel Webster petitioned in vain for the extradition of the slaves who mutinied aboard the Creole and had become free, according to British officials, by virtue of landing in Nassau in the British Bahamas.137Close West Indian Emancipation had radically reshaped the boundaries of freedom and slavery throughout the Atlantic world. Indeed, in 1851, the French National Assembly declared slavery and the imprisonment of black sailors to be “barbarous,” as Great Britain continued its fruitless negotiations with the intractable South Carolina Assembly. “Neither France nor England,” France’s General Lahitte reportedly declared, “have been able to persuade the government of the United States to enter into the ways of civilization and humanity, which we will persevere to march in.”138Close Lahitte’s disdainful words chart the Enlightenment’s unfinished journey from Europe to the so-called New World as France and Great Britain began to reshape themselves as free nations in the wake of abolition and emancipation.139Close

Fresh from governorship of the Bahamas, George Buckley-Mathew, the British consul-general of the Carolinas, initiated diplomatic negotiations with South Carolina’s Governor Means in “hopes that the law by which any of H.B.M.’s subjects are taken from the protection of the British flag and imprisoned, should not be extended to foreigners.”140Close Charleston police officers had seized Isaac Bowers, “a coloured man, a native of Antigua, and, of course, a British subject,” and incarcerated him for two months while his vessel Mary Ann was refitted for its transatlantic journey.141Close Bowers was the first of three highly publicized cases of British seamen who were incarcerated and, in one instance, sold into slavery by the Charleston police. Over the next few years of heightened protest, transatlantic antislavery print culture freely disseminated these stories as powerful symbols of slavery’s inexorable workings, leading to the law’s modification in December 1856.142Close The British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society addressed a memorial to Palmerston, the British secretary of foreign affairs, urging the government to take more active measures to prevent the ongoing violation of “the just liberties of a large body of mariners,” after it determined that Bowers was “not likely to obtain any redress for the indignity and injury he … suffered at the hands of the American authorities.”143Close Public interest was further aroused when, after returning to Britain, Bowers brought suit against his former captain for withholding wages “on the ground that he had paid for the steward’s support while in gaol.”144Close The prosecuting attorney condemned Capt. William Waddington for his passive acquiescence to “the unjustifiable imprisonment of Bowers,” since he had “made no representation to the British Minister at Washington City, or even sought the protection of the British Consul.”145Close The combined efforts of mariners such as Bowers and Anglo-American abolitionists intensified public protests, forcing Parliament to take more-active measures to secure the repeal of those “obnoxious laws.”146Close “[P]ublic indignation in [Great Britain] had been greatly excited by the statements in the newspapers,” and Palmerston was asked to satisfy the “people … that the Government … [would] take any practicable steps towards remonstrating against and putting an end to the practice in question.”147Close

Under this public pressure, Palmerston issued yet another appeal to the U.S. government on behalf of the “plain rights of British subjects.”148Close U.S. Secretary of State John Clayton, unwilling to interfere in a “local” concern, referred British Consul Mathew to Governor Means. Newspaper accounts of Mathew’s rather unprecedented private negotiations with Means out-lined the long unresolved conflict between South Carolina’s local laws and the federal treaties between Britain and the United States.149Close The British press denounced the violation of Bowers’s rights as a free Englishman, even though it generally cautioned against extreme diplomatic measures, unlike the radical position of Littell’s Living Age, which condemned the “gratuitous imprisonment of a whole class of British subjects” as amounting “to a diplomatic grievance of the first magnitude.”150Close The editor of Littell’s even demanded reparations for the imprisonment of all British crewmen whose “complexion falls below a recognized standard of olive” as “amends for the insult put upon our colored fellow-countrymen.”151Close The vexed status of black Britons that had been raised in Elkison reemerged in postemancipation Britain as the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society urged the government to “do its duty” to protect the “personal freedom of all British subjects, without distinction of colour.”152Close

The South Carolina legislature remained obstinate, even though Louisiana, pressured both by popular opinion and by its British consul later that year, “passed an act amending the colored law of the State, by abolishing the penalty of imprisonment, and permitting free persons of color to come on shore, with passports from the Mayor.”153Close Failing in various appeals to the South Carolina legislature, Mathew, at the direction of the charge d’affaires in Washington, decided to challenge the “police law” through the courts. He began legal actions on behalf of two recently arrested black seamen, Manuel Pereira, a Portuguese sailor articled to service on the English brig Janson, and Rueben Roberts, a native of Nassau in the British West Indies and cook aboard the English schooner Clyde. It is likely that the two men shared the same Charleston jail cell. Although South Carolina’s Negro Seamen Act, as a number of newspapers noted, was “to be tested in more forms than one,” the proximity of the two cases yielded reportage that confused the specifics of their separate proceedings.154Close Pereira’s case was particularly effective at sensitizing British and American publics because his vessel had been “driven into the port of Charleston in distress,” and the wrecked condition of the Janson’s arrival in Charleston Harbor was key in Pereira’s case against the police law.155Close Newspapers ranging from the London Times to the Liberator noted that Pereira’s incarceration was particularly repugnant because of “the involuntary character of his visit to the shores of Carolina.”156Close Even the Charleston Mercury admitted, albeit with some ambivalence, that the police law “was passed to reach only those cases in which the party subject to it, voluntarily came within the jurisdiction in defiance of its provisions.”157Close Consul Mathew engaged Charleston native and former Attorney General James L. Petigru, who appealed Pereira’s case to the state supreme court when the lower court refused to issue a writ of habeas corpus. The South Carolina Supreme Court postponed the hearing of the appeal to the following year, forcing Pereira to “lie in jail” for eight months.158Close The South Carolina jurists, no doubt, calculated that the case would fail once Mathew obtained Pereira’s release. “If Pereira is now released by paying the charges,” speculated newspapers, “the case and the prospect of obtaining from the final authority a decision upon the question will fall to the ground. And it would be hard to keep the poor fellow immured long enough for the argument to be had at Charleston, and the decision rendered, so that an appeal may be taken to the Federal Judiciary.”159Close

The local media and Charleston police officials disseminated distorted versions of Pereira’s arrest. These accounts neglected to note that the Janson had been wrecked; neither captain nor crew had a vessel to which they could return. Arrested on 24 March 1852, Pereira was thus left to face the prospect of an indefinite imprisonment and eventual enslavement. Given these unusual circumstances, Mathew, acting “under instruction from his Government, to test the Constitutionality of the act,” began the legal actions on Pereira’s behalf.160Close Governor Means, by his own admission, had specifically directed the Charleston sheriff “not to give up the prisoner even if a writ of habeas corpus had been granted … while these proceeding were pending,” even though he later contradicted himself in claiming that Pereira “was at perfect liberty to depart at any moment that he could get a vessel to transport him beyond the limits of the State.” As the Anti-Slavery Reporter noted, Means left unanswered the key question of “[h]ow the unfortunate prisoner was to ‘get a vessel,’ under these circumstances.”161Close As Mathew took steps to appeal Pereira’s case before the state supreme court, the Charleston sheriff, hoping to prevent further legal action, “made an attempt to ship Pereira off,” since “his presence was essential to test his right to the habeas corpus” (MP, 355, 358).162Close Mathew, “finding that his great object would thus be defeated, intercepted the sheriff, on his way to the vessel,” and paid Pereira’s passage to New York once they completed “the requisite arrangements for carrying on the suit in appeal.”163Close Mathew was misadvised, however, and Pereira’s case was eventually struck from the docket of the state court in 1853 on the grounds that he was no longer in custody.164Close

While awaiting Pereira’s delayed hearing, Mathew directed Petigru to charge Charleston sheriff Jeremiah D. Yates in the U.S. circuit court for the “assault and false imprisonment” of Rueben Roberts, asking for damages in the amount of four thousand dollars “for the indignity which he had suffered.”165Close Sheriff Yates had seized Roberts from the Clyde upon its arrival from Cuba on 19 May 1852 and jailed him for one week until the vessel was ready for sea.166Close The U.S. circuit court judge in Charleston declared the South Carolina law valid when Roberts v. Yates (1853) came to trial, and the case was ready for appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court once the jury decided in the sheriff’s favor.167Close The New-York Daily Times offered a biting commentary on South Carolina’s Negro Seamen Act when Roberts’s case made international headlines: “Satire could hardly select a fairer mark for mirth than the spectacle of a sovereign State, represented by a Sheriff and his posse, bearing down upon every arriving merchantman, inspecting the crew, and claiming the custody of all persons, whose complexions justified a suspicion of African descent.”168Close A number of newspapers saw these two cases as the culmination of decades of thwarted efforts to test the “validity of the law,” a pattern of obstruction intensified since Samuel Hoar’s expulsion from Charleston.169Close Many people entertained hopes for the law’s imminent repeal once either of the two cases entered the U.S. Supreme Court docket; however, Roberts’s case, like Pereira’s, never came before that federal tribunal.

Fear of rupturing amicable trade relations with the United States prompted the British government to adopt a more judicious course to conciliate South Carolina.170Close By June 1853, it had elected to drop both lawsuits and instructed Mathew to withdraw Roberts’s appeal, which was pending trial before the U.S. Supreme Court.171Close Commercial interests and the British government’s unwillingness to further aggravate U.S. sectional tensions, combined with a new and less interventionist-minded British Foreign Secretary, facilitated this diplomatic course.172Close The National Era reported that the U.S. federal government had advised Britain that “to insist on the repeal of those laws under which the imprisonment of colored foreigners, entering South Carolina, would raise questions between the slave States and the Federal Government which would be exceeding inconvenient, if not destructive to the Union.”173Close Unwilling to foment ill will with the United States, Britain announced “that the Law officers of the Crown were satisfied that Great Britain had no ground for complaining of any infraction of treaties.”174Close In a November address before the state legislature, the South Carolina governor confirmed that “the cases of manuel pereira and reuben roberts, colored seamen, are settled.” South Carolina officials undoubtedly thought they had put to rest “the awkward case … that has been before the British and American public in more shapes than one.”175Close They could not, however, expunge Pereira and Roberts from public memory, and, in the failure of law and diplomacy, a relatively unknown British writer, F.C. Adams, brought their cases before “the bar of public opinion” for proper adjudication.176Close

Manuel Pereira; or, The Sovereign Rule of South Carolina was the first of a number of popular antislavery historical fictions written by the former Savannah Georgian newspaper editor F.C. (Francis Colburn) Adams.177Close From the little that can be pieced together of his biography, Adams was “an Englishman … [who] resided many years in the Southern States” and had been, according to the Anti-Slavery Reporter, “[o]fficially connected with one of the principal local journals, but was finally turned against slavery by what he witnessed of its atrocities.”178Close An unverified account in the Zion Herald claimed that Adams

resided in Charleston, where he was treated with much consideration until he took part with the British Consul Mathew in his opposition to the law imprisoning colored seamen. It was, we understand, for this offense that Mr. Adams was thrown into prison, on his release from which he went to London, in 1852, where the publication of “Our World,” a novel, and other works illustrative of southern life, have given him considerable reputation in the department of literature which has been illustrated by the genius of Mrs. Stowe.179Close

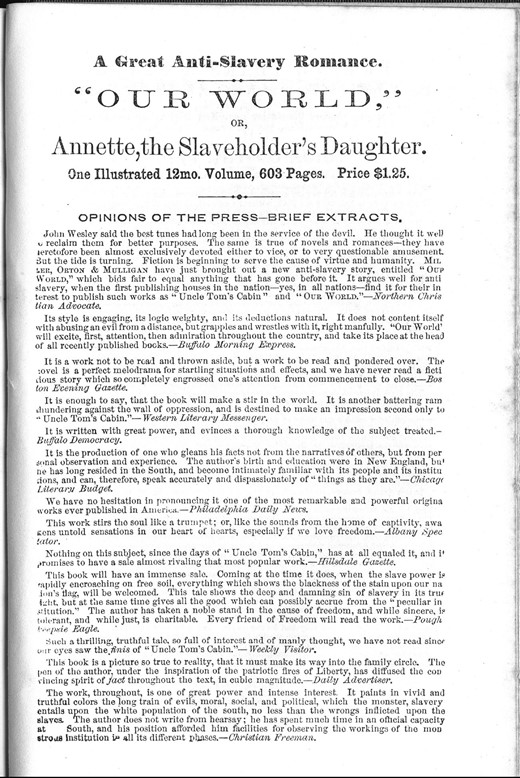

Indeed, the New York publishers Miller, Orton & Mulligan advertised Our World as “A Great Anti-Slavery Romance” in the back pages of Kate Pickard’s The Kidnapped and the Ransomed (see figure 4.2). The particular regional cadences and sectional politics of the antebellum United States fascinated Adams even after his return to Britain, and he captured them in a number of short and full-length works.180Close Advance praise from the New-York Daily Times for Adams’s third novel was particularly descriptive of his penchant for seizing on records and documents to craft compelling histories of the present, touting Justice in the By-Ways, another novel set in antebellum Charleston, as “emphatically a work of our age…. a history in the guise of fiction, history whose accuracy is attested by public records and State documents. Each character is a living reality.”181Close Manuel Pereira, likewise, offered readers the merits of a legal treatise in the form of a “life-like” ethnographic fiction.

Advertisement for F. C. Adams’s antislavery fiction Our World; or, Annette, the Slaveholder’s Daughter. Taken from the back pages of Kate E. R. Pickard’s The Kidnapped and the Ransomed.

Buell & Blanchard of Washington, D.C., first published Manuel Pereira in the spring of 1852, as the international disputes over the South Carolina regulation became more heated, and the London publishing house of Clarke, Beeton, & Co. republished the novel the following year.182Close Buell & Blanchard placed a number of advertisements for the novel in its abolitionist weekly National Era, which had just completed its serialization of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.183Close The National Era favorably commended the novel to its readers and described the work, then in press, as

founded upon that infamous statute of South Carolina, by which her citizens claim a right to imprison colored seamen, of all nations, and even those cast upon their shores in distress. We have perused the book in advance of its publication, and find that it gives a life-like picture of Pereira … the prison regimen, character of the Charleston police, and the mendacity of certain officials, who make the law a medium of peculation.184Close

The novel’s topical subject matter, the reviewer insisted, “cannot fail to interest alike the general reader, commercial man, and philanthropist”—much like the unlikely and shifting coalitions forged among free blacks, abolitionists, diplomats, and merchants had in protest of the police law over the preceding decades. As a man “raised and educated in the spirit of her institutions,” Adams’s autobiographical introduction establishes his personal allegiance to the regional South only to make his subsequent critique of the Negro Seamen Act as an “effect of slavery and its wrongs” all the more damning (MP, vii). Manuel Pereira begins, deceptively, as a nineteenth-century ship narrative in the fashion of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick or Edgar Allan Poe’s Arthur Gordon Pym, only to become a rather dark eyewitness exposé of the capricious workings of criminal justice in Charleston. Indeed, Manuel Pereira challenges the romantic radicalism of current Atlantic historiography with its perverse stress on the racialized forms of containment rather than the mobile freedoms generally associated with sailors and maritime life.